The Herring Girls

Herring were, for millennia, essential to survival in the coastal regions and islands of the North Atlantic where the cultivation of crops was limited. Such was the bounty of this food source that a thriving industry developed over the centuries. Herring were cured and exported in huge quantities to Russia, Northern Europe and North America. This industry provided employment for fishermen, coopers and thousands of “Herring Lassies” for generations.

Throughout the 19th and into the mid-20th century almost every family in the Outer Hebrides was involved in the industry to some degree. For some – my own family included – it was their main source of income. My two grandfathers co-owned a herring drifter called the Home Rule, and all of the male members of my parents’ families were fishermen, including my father who began his working life, like his brothers, at the age of fourteen.

I had three aunts who were Herring Girls in their youth, and I had the good fortune to hear them recount their first-hand experiences of their work at home and “abroad” as they travelled the island and coastal “herring trail” from North-West Scotland to Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft in East Anglia in the 1920s and 30s. At every spare moment the Herring Girls knitted gansies and shared their expertise with one another. My aunties were delighted to pass that expertise to me when as a child, as I always showed an interest in this fascinating form of creativity. You can listen here to a very brief outline of the herring industry and of some of my aunties’ experiences as Clann-Nighean an Sgadain (Herring Girls).

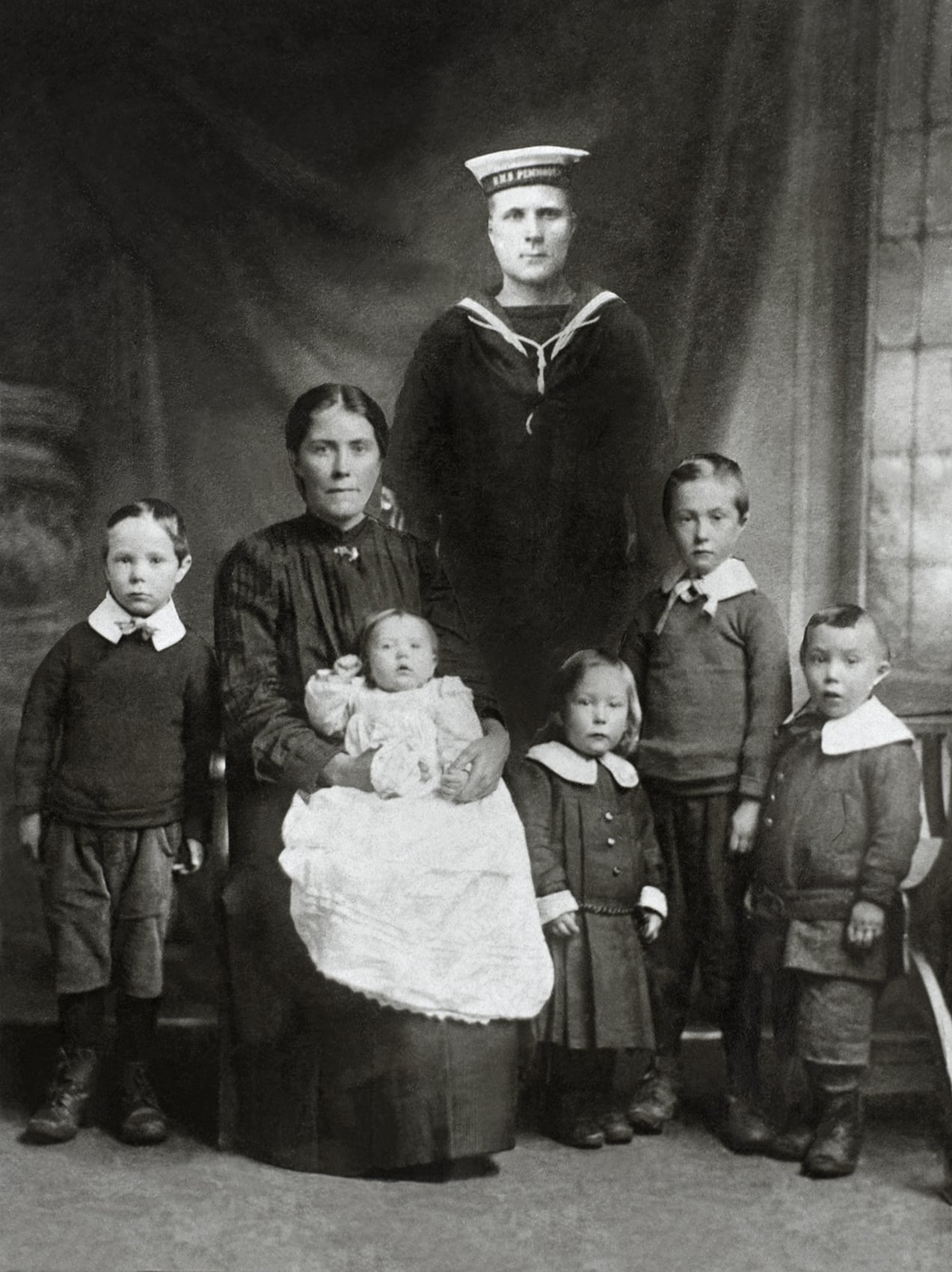

The Hebridean culture was centered around the fishing industry, which can be seen clearly through my own family photographs.

Above left is a family photograph taken toward the end of WWI. My grandfather Alexander Matheson stands at the centre of the image in his naval uniform. As you can tell from the lighting and definition, he was not actually present; his image was transposed from another picture. Century-old darkroom tricks allowed a family portrait despite the separation of war. My grandmother Isabella, is holding my uncle Malcolm and she was likely pregnant with her sixth and youngest child Alasdair at the time of the portrait. My father Thomas stands on the far right, wearing his little tweed outfit, and my aunt Alexanderina (known as Shonag from early childhood) stands in front of her father. My uncles Norman on the right, and Angus on the left, are wearing simple gansies rendered "Sunday Best" with the addition of starched white collars.

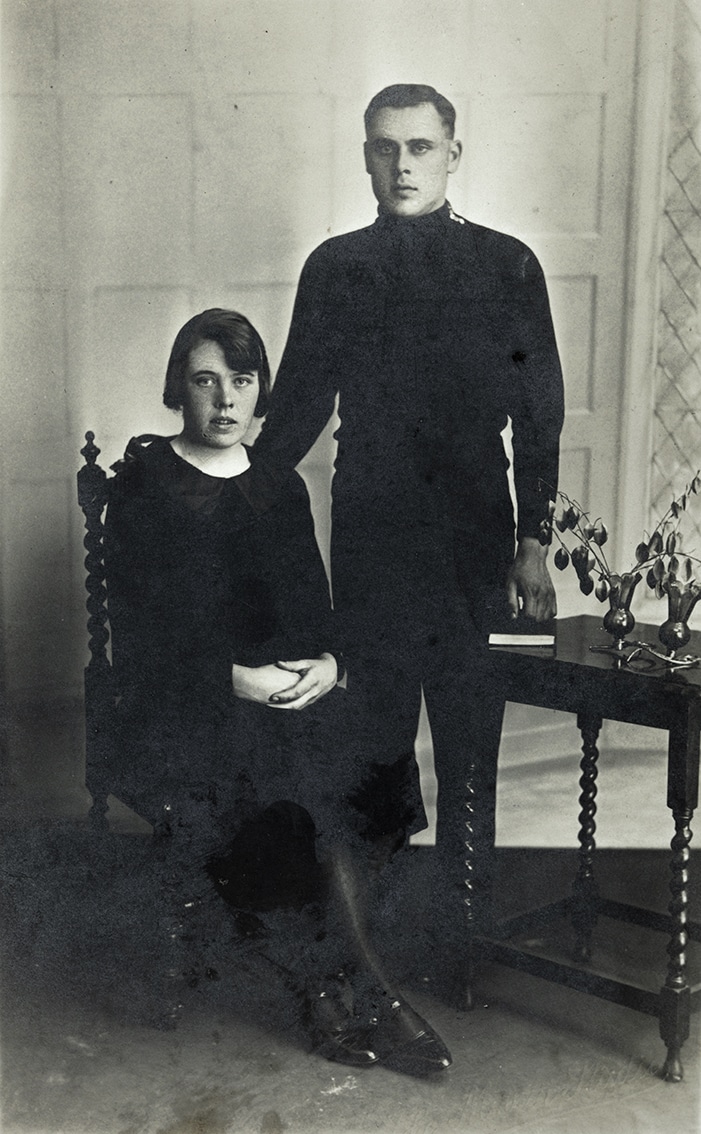

Above right, are my maternal aunt and uncle, Ishbel and Donald Macleod. This image was taken in Great Yarmouth at the end of the fishing season. Herring Girl Ishbel is wearing a pair of brand new shoes, which along with the portrait itself would have been a treat on receipt of her wages. Donald, who was a fisherman, is wearing one of her gansies.

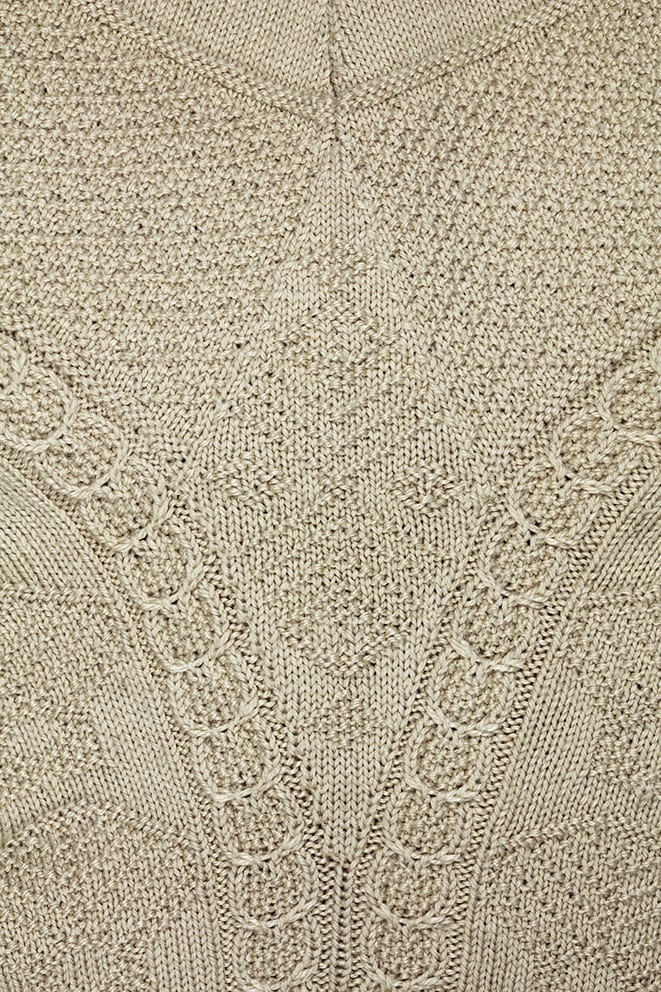

Below centre, is my father Thomas, working as a fisherman on the herring drifter Windfall, out of Stornoway harbour. He is wearing a button-necked gansey knitted by his sister Shonag (below right), who worked as a Herring Girl before her marriage.

Below left, is a portrait of myself taken at the shoreline at the foot of my croft. I am wearing one of my own gansies and demonstrating the use of a knitting belt. You can see a Video Tutorial showing how to make and use a knitting belt here.

Above and below left, my aunt Shonag's great-grandaughter Beth, wearing two of my gansey and stranded hat set designs.

Below right, Shonag on her wedding day.

Being a Herring Girl involved meeting, working and knitting gansies with girls from all the North Sea coastal ports and so there was a great enjoyment to be had in sharing patterns and ideas. I was delighted that my aunties enjoyed the patterns I created for the gansies in my book Fishermen’s Sweaters. They particularly liked the new idea of the star I designed for my Eriskay, and the fact that it was a reference to my married name.

I designed Cape Cod specifically to honour all the women who knitted gansies for their menfolk and so I was very proud that my aunties appreciated its femininity and the idea of shells as pattern imagery. They did find the notion of patterned underarm gussets amusing and – being practical in nature – they wondered why I went to such trouble for something that was largely hidden from view. Though they never said so, I suspect they thought it came from having too much time on my hands.

The herring industry suffered great decline from over-fishing by huge modern trawlers during the latter decades of the 20th century. The independent fishing boats working from Stornoway harbour now land mainly whitefish and shell fish. But Clann-Nighean an Sgadain are not forgotten and two beautiful sculptures – accurate in every detail – honour them at the North and South Beaches of the harbour where once hundreds of boats landed their catches of Silver Darlings for the Herring Girls to cure.