The Queen of the Waves

It is evident from the extensive archaeology on Hiort that in spite of its remote and forbidding location, people travelled to and fro for many centuries, if not thousands of years. One has to be a good sailor to get there, unless a rare spell of calm weather quells the Atlantic. But even a fair wind makes for a rough crossing and there is always the possibility of not being able to make it to shore; the wind direction and ocean swell frequently makes Village Bay too dangerous for landing.

For the islanders, the ocean was a hazard to be faced with caution and courage in equal measure. Any visitor faced with the reality of the enormous jagged cliffs rising out of the heaving ocean can only be humbled by the islanders’ ability to make this truly awesome place their daily working environment. They were born to it and even young girls went out in boats and climbed the sheer stacs and cliffs of Boreray, Soay and Dùn to harvest food. When necessity dictated, they also crossed the ocean and made the best of whatever lay before them. I see their legendary heroine as a facet of all the women of Hiort and so my ideas for the Queen of the Ocean will be informed by their lives and their relationship with the Atlantic, which to them was both a resource and a means of travelling on with courage and hope.

My father was a fisherman from age fourteen to his forties, and his tales from various ports of call were very entertaining. His most terrifying tale was of a visit to Hiort. On a calm day of rest he took his vessel’s small rowing boat for a spin beneath the towering cliffs, and on a whim he decided to visit one of the caves, of which there are many. During his exploration he inadvertently found himself in a small cave suddenly cornered by the biggest and most aggressive bull seal he had ever encountered. He had only an oar for his defence and after a struggle he finally managed to repel the beast and give himself enough space to beat a hasty retreat.

I made this sporran in memory of his story, which used to scare the daylights out of me, not least because I knew the size of a bull seal’s sharp teeth. This sporran, filled with suitable charms and tokens, will make for a peaceful passage over the ocean. This is an idea for something that may worn by a traveller from one island to another.

I have called it Skildir as I think it suits the name, and this is the name from which St Kilda derives. There was never any saint and it seems that the name St. Kilda came about through an error by an early cartographer who inserted a stop between the S and the K of Skildi – a Norse word meaning “shields”. It is worthy to note that from a distance the islands can appear to sit on the ocean like Viking shields.

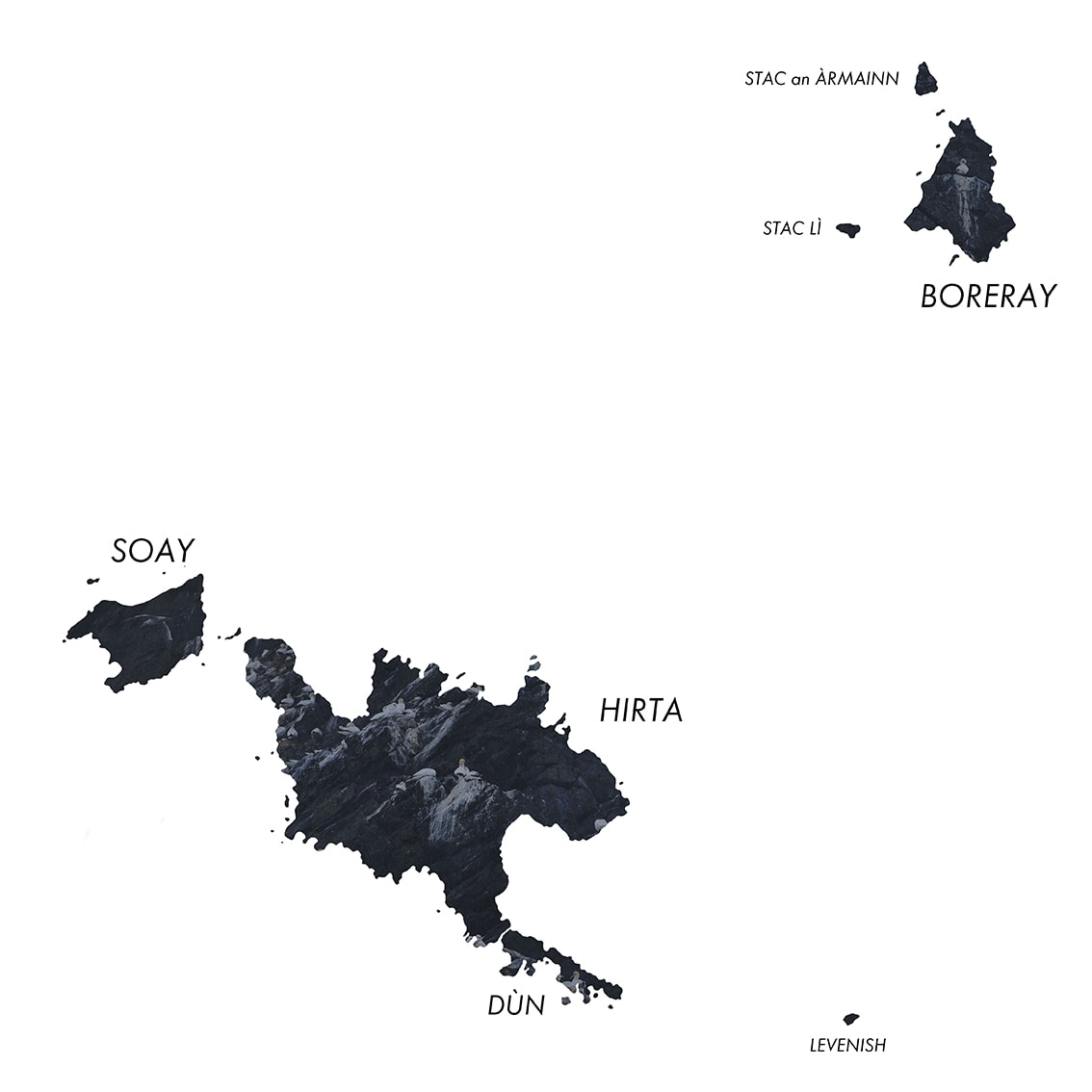

Conachair is the highest hill on the main island, rising up protectively along with its neighbour Mullach Mòr, to shelter Village Bay from the north winds. Viewed from the bay, Conachair (below) presents a rounded, comforting shape that belies the heart-stopping drama of its north face: its 430-metre cliffs dropping straight down into the ocean are the highest sea cliffs in the British Isles. From the summit it is possible to mentally trace the shape and size of the rim of the volcano by turning and viewing each island and stac in the archipelago. It then becomes clear that the core of the volcano lies under An Linne, the four-mile wide deep-water ocean pool between the main island of Hirta and Boreray.

As if the unique beauty of the archipelago seen from the summit of Conachair were not enough, the wonders that lie hidden beneath are also truly extraordinary. The underwater scenery is spectacular with huge tunnels, gullies and arches filled with marine life such as technicolour jewel, plumose and sagartia anemones and myriad soft corals and sponges. This underworld has only been revealed to man in the last 40 years or so, but it has been familiar to Hiort’s seabirds from time immemorial. Their view ranges from the heights to the depths and watching gannets rising up in the air to a height of 30 metres and then making arrows of themselves to dive straight down at a speed of 100kmph is exhilarating even for the watcher.

Imagining what sights the gannets see as they plunge down through the clear water was the starting point for this particular sketch in wool. I was also thinking of the close relationship the women of Hiort had with the seabirds and of the incredible risks they took to hunt and gather, so I made this sketch as a sheath that can be used to carry a knife or other useful small items, such as knitting needles, which they were rarely seen without. I started by knitting the shape in sea colours. I then felted the piece so that the colours meld from dark to bright, rather like light on waves, and then covered the piece with abstract embroidery based on the intensely colourful undersea life. I knitted seaweed tassels and twisted cords to depict the ropes so vital to human life on the cliffs and sea. I plan to extend this into other items for my Hiorteach Queen of the Ocean.